|

Do you have something

happening in your corner of Washington? - Please call a member

or e-mail your observations to have them included here

December:

Picture by Jed Schwartz

Does this look like December in Washington, NH?

Warmth befuddles wildlife

Wildlife biologist Eric Orff had the enviable job Wednesday of flying across the scenic waterways of Great Bay and the Isles of Shoals.

Each year he takes the trip to count the number of ducks and geese wintering along the shores.

This year, said Orff, the number is half of what it was last year. The usual migration from Canada has yet to happen. Geese and ducks that summer here have yet to depart. It's due to the unusually warm winter this season.

Normally Orff counts around 3,000 geese, 3,000 ducks and 500 common eider. On Wednesday, he counted 3,446 ducks and geese combined and 184 eider.

"They're still in their summer range," he said. "There's so much food. It's kept the northern birds from flying down. The resident birds haven't gone anywhere."

The lakes are still open, bears are not hibernating, squirrels are starting to chase each other in a mating dance that usually doesn't begin until late January, and even frogs were heard two weeks ago, Orff said.

Usually bears go into hibernation around mid-November, he said. Frogs seek out wetlands and ponds to sleep through the winter by early October.

"Last winter and this winter, I got a number of calls of bears still active," Orff said on Tuesday. "Today I heard about some in the Conway area."

There's more non-migratory robins that stay the winter. That's been going on for more than a decade, he said.

In the North Country, snowshoe hares have changed color from brown to white, making them more vulnerable to predators.

Orff has been a wildlife biologist for the state Fish and Game Department for more than 30 years, working out of the Regional office in Durham.

This year is somewhat similar to last year, he said, when the lack of a cold January all but cancelled ice fishing on the Exeter and Swampscott rivers.

Economically, it hurts any business that depends on snow and ice, such as snowmobile dealers, sport shops, the ski industry and Fish and Game, which gets revenue from selling ice fishing licenses.

Short term, wildlife has benefitted from the warm temperatures. Mice may have no snow cover in which to hide, but that benefits hawks and other predators.

Over the long term, the warm weather could have dire consequences, according to Orff: more outbreaks of disease in humans from ticks that carry Lyme disease, and in plants from the gypsy moth. Cold generally kills the pests.

The warm weather will allow more young animals to live, which may hurt populations later. Typically, a tough to severe winter kills up to 60 percent of newborn animals, said Orff.

"I've had folks tell me some of their spring flowers were already in bloom like crocuses," said Orff. "No doubt the natural cycle of our fields and forest will be changed."

"I think a lot of us are watching wildlife and nature and are concerned," Orff said. "Is this really global warming or an anomaly? This is something that is dramatic. Global warming isn't some abstract thing, it's what I observe on a daily basis."

State climatologist Dr. David Brown said he sees a trend in warmer winters.

Brown is also an assistant professor of geography at the University of New Hampshire.

"It appears to have been the warmest December in Concord since 1950," said Brown.

The lack of snow pack will affect water run-off in the spring.

"The hydrologic balance will be out of whack for the rest of this winter anyway," Brown said. "I don't necessarily think a swing to cold temperatures would right the shift."

Winter temperatures not only this season but in recent years is up 2 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit over 1970, said Brown. The difference between a 30-degree day and one that's 34 degrees can make the difference between rain and snow.

"It's definitely part of a trend," he said. "There's no question we've seen an upward temperature trend in the last three or four decades. It's representative of what's happening across New England and globally."

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has done climate predictions for the rest of the season, said Brown.

"Their current projection is for above normal probability for warm temperatures into March," he said, "with precipitation, no strong indication one way or another. The warm weather is potentially going to continue."

Information found here:Seacoast Online

November:

Picture credit: The Weather Network

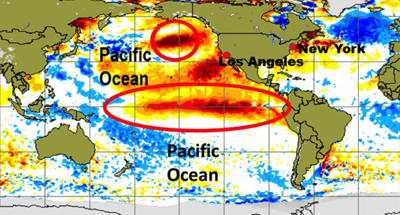

We are in the midst of a rapidly strengthening El Niño event which will likely peak later this fall as one of the strongest El Niño events on record! So, what does this mean for the upcoming winter season?

El Niño is associated with a warming of sea surface temperatures in the tropical regions of the Pacific Ocean, primarily to the west of South America (region highlighted by the oval on the map below). When ocean water temperatures in this region are warmer than normal, it impacts weather patterns around the world, especially during the late fall and winter. As we head into winter, El Niño will likely peak as one of the top two strongest events since 1950.

El Niño has a reputation for bringing mild winters to much of the country, especially across the northern States. The two strongest two El Niño events on record prior to this year (1982-83 and 1997-98) were quite mild from the Pacific Northwest to the Northeast. Only the Southwestern States saw below average temperatures during those winters.

However, a review of other El Niño winters shows that a strong El Niño does not guarantee a mild winter. We do think that this winter will start off rather mild across most of the country. The map below with our forecast for December (and likely into early January) looks a lot like the El Niño winters of 1997-98 and 1982-83. However, we do not expect that this mild pattern will persist through the entire winter.

Later in the season, especially during February, we expect several weeks of classic winter weather over the eastern third of the country. This period will likely feature several winter storms from the south central Plains to the Northeast, with a higher than typical threat for significant snow and mixed precipitation deep into the South.

Across the Great Lakes and Northeast, the mild start to winter will be offset by the colder conclusion to winter and result in temperatures that are close to normal. Nearly all El Niño winters in the past have featured an active storm track across the southern United States, with a turn up the East Coast to New England. It looks like that pattern will dominate our winter this year as well. Therefore, we expect above-average precipitation from Southern California to Florida and up to the East Coast to Maine.

So far this prediction is correct, the fall has been mild here in Washington, it will be interesting to see how the rest of the winter plays out. Another key is whether El Niño peaks later this fall and then starts to weaken as we progress through the winter or whether it continues to strengthen during the winter. A strengthening El Niño rather than a weakening El Niño during the heart of winter would likely mean a milder winter for the Northeastern States. Stay tuned!

Information found here:The Weather Network - A Tale of Two Seasons

October:

Picture credit:Yeliseev/Flickr Creative Commons

Doug has a pair of Ravens hanging out around his farm. We wondered what was the difference between ravens and crows.

Crows and ravens, although in the same genus (Corvus) are different birds. In general, the largest black species, usually with shaggy throat feathers, are called ravens and the smaller species are considered crows.

Common Ravens can be told from American Crows by a couple of things. The size difference, which is huge, is only useful with something else around to compare them with. Ravens are as big as Red-tailed Hawks (about 24-27 inches), and crows are, well, crow sized, they average around 17 inches long. The wedge-shaped tail of the raven is a good indicator, you can see it in flight. Crows have a shorter tail that is rounded or squared off at the end.

More subtle characters include: ravens soar more than crows. If you see a "crow" soaring for more than a few seconds, check it a second time. Crows never do the somersault in flight that Common Ravens often do, they can even fly upside down. Ravens are longer necked in flight than crows. The larger bill of the raven can be seen in flight, but it is actually less apparent than the long neck. Raven wings are shaped differently than are crow wings, with longer fingers with more slotting between them. It is said, "Ravens are the ones whose wings you can see through." The longer fingers make the wings look more bent at the wrist than a crow as the bird flies, and the "hand" portion can look nearly pointed.

If seen perched, the huge bill and shaggy throat of a raven are distinctive. The upper and lower edges of the bill are parallel for most of their length in ravens, while in crows the downward curve starts somewhere around 2/3 of the way out for males, and about halfway for females.

American Crows make the familiar "caw-caw," but also have a large repertoire of rattles, clicks, and even clear bell-like notes. However, they never give anything resembling the most common calls of Common Ravens. The most familiar call of a raven is a deep, reverberating croaking or "gronk-gronk." Only occasionally will a raven make a call similar to a crow's "caw" but even then it is so deep as to be fairly easily distinguished from a real crow. Ravens also make a huge variety of different notes. It has been said (attributed to native Americans) that if you hear something in the forest that you cannot identify (assuming you know all the common forest sounds), it is a raven.

The crow is very social and will hang out in large flocks. Common Ravens aren’t as social as crows; you tend to see them alone or in pairs. Inquisitive and sometimes mischievous, crows are good learners and problem-solvers, the Raven is also very intelligent and is the largest song bird in North America.

The common raven does not migrate they stick around for the winter.

Information found here:Cornell University - Raven Facts

and Cornell University - All About Birds, Crow

and Cornell University - All About Birds, Raven

September:

Picture credit: Flickr/Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren

Picture credit: Alex Lamoreaux

In the last few weeks both Arin and Doug saw large flocks of Nighthawks in East Washington and Hillsboro. They are migrating right now and are a rare sight.

The common nighthawk is not really a hawk. It is actually a member of the nightjar family. The nightjar family includes the whip-poor-will and the common poorwill. The common nighthawk is a jay-sized bird about 10 inches in length. It has mottled grayish-brown feathers, a long forked tail, and long pointed wings with a broad white wing bar. The common nighthawk has a large mouth with bristles that help it catch insects. Males have a white throat patch and a white tail bar. Females have a light brown or cinnamon colored throat patch and no tail bar.

While in flight, the common nighthawk catches flying insects like flying ants, mosquitoes, moths, and grasshoppers. It feeds at dawn, dusk, and at night. It sometimes feeds during the day, especially if it is overcast. It is sometimes called the mosquito hawk!

Mating season runs from April through July. The nighthawk doesn't build a nest. The female lays from 1-3 eggs on the ground in an open gravely or lightly vegetated area. In cities and towns, she often lays her eggs on a flat gravel-covered roof. The female incubates the eggs for about 19 days. The chicks can move about on their own shortly after birth, but they are fed by both their parents for about a month. They start to fly when they are around 23 days old.

The common nighthawk is found in open woodlands, clearings, and fields. It is also found in towns and cities. The common nighthawk has adapted to city life. Flat roofs make good nesting spots. Baseball fields and other open areas that have artificial lights attract insects, making them good hunting spots for the common nighthawk.

The common nighthawk is an endangered species in New Hampshire. Scientists believe this may be due to nesting habitat loss and increased use of insecticides that kill the insects that the common nighthawk needs to survive.

Project Nighthawk is a statewide research initiative, coordinated by New Hampshire Audubon, aimed at conserving a state-threatened bird species, the Common Nighthawk.

More information about this project is available here: NH Audubon Project Nighthawk

Information found here:NH Public TV

August:

Picture credit: National Geographic Kids

A woman in Ashuelot called to say she had a young Peregrine Flacon hanging out in her yard. This is quite unusual. They breed mostly in the White Mountains, with a few pairs further north and one to the south in Manchester. They may be seen during fall migration which peaks in early to mid October.

In NH, their conservation status is threatened, but federally their status is not listed; which means that Peregrine falcons are legally protected in New Hampshire. the possession and take (which includes harming, harassing, injuring and killing) is illegal.

The Peregrine Falcon is also know as the duck hawk. They are a large bird; 14-19” long with a 39-43” wingspan. They have a blue-gray back, barred white or buff color underneath, and a dark head with black sideburns. They can be commonly confused with the Merlin, which are similar in color but smaller in size.

They are found in a variety of habitats, most with cliffs for nesting and open areas for foraging, but are also found in large cities where it nests on buildings. Open landscapes and air spaces, where peregrine falcons can locate and attack their prey in the air, are important components of most habitat types. Preferred habitats include mountainous terrain, agricultural land, wide river valleys, lake shorelines, ocean coastlines, and islands.

Peregrine falcons begin breeding at one year of age and pairs mate for life. The females nest during March to May and lay 2-5 eggs. The young hatch after about 30 days of incubation and chicks are able to fly when they are 35-42 days old.

They feed mostly on medium-sized birds, but may also prey on small mammals and reptiles. It is a very fast flier especially in pursuit of prey which they catch in flight.

The state has a Peregrine Falcon Project with a goal to annually monitor the peregrine falcon nest sites and to obtain measures of population status and productivity. The partners areNH Fish and Game, New Hampshire Audubon and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They found that in 2008, New Hampshire had 16 pairs of breeding peregrine falcons. Thirteen of the pairs successfully raised a total of 27 young this year. A grand total of 360 peregrine falcon chicks have fledged from New Hampshire since they first began breeding in the state again about 27 years ago. The project website is found here: NH Wildlife Non-Game project

Information found at: NH Fish and Game and at NH Fish and Game profiles

July:

Picture credit: Bruce Marlin

Phil and Arin saw an intimidating looking female Giant Ichneumon Wasp (Megarhyssa macrurus) on their porch railing. They thought it had the longest stinger they had ever seen on a bug! This large wasp has a tremendously long ovipositor for egg-laying, not for stinging.

The wasp has a reddish-brown body approximately 2 inches long with black and yellow-orange stripes. Its wings are transparent and the body elongated. The female of this species has an ovipositor of approximately 4 inches in length. She is very impressive!

It is a predatory insect, notable for its extremely long ovipositor. It uses this to deposit an egg into a tunnel in dead wood bored by another species of wasp (the larvae of the pigeon tremex horntail). Another of its common names is 'stump stabber' referring to this behavior.

They are considered harmless to humans; they are parasitoids on the larvae of the pigeon horntail (Tremex columba), which bore tunnels in decaying wood. Female Giant Ichneumon Wasp are able to detect these larvae through the bark, and lay their eggs on them; within a couple of weeks, the wasp larvae will have consumed their host and pupate. They will emerge as an adult the coming summer.

They are found only in North America.

Information found at: Wikipedia

June:

Picture found at Missouri Audubon, credit: Jim Williams

Jed was alerted to the presence of an American Bittern in a wetland area in town. We went out to take a look and got a memorable sighting of this bird. We heard the bird before we saw it, its booming voice carried far over the wetland!

Extensive freshwater marshes are the favored haunts of this large, stout, solitary heron relative. It is seldom seen as it slips through the reeds, but its odd pumping or booming song, often heard at dusk or at night, carries for long distances across the marsh.

The Bittern is a medium-sized wading bird that is 23-34 inches in length with a wingspan of three feet. It is dark brown on its uppersides and its underparts are streaked with brown, tan and white. Its stripped appearance blends with its habitat very well. It will stand very still with its beak raised, looking just like the reeds surrounding it and is very hard to spot.

Their call can be heard on their breeding grounds and is a loud pumping sound, "oong-KA-chunk!" repeated several times and often audible for half a mile. Its flight call is a low "kok-kok-kok".

The Bittern forages mostly by standing still at edge of water, sometimes by walking slowly, capturing prey with sudden thrust of bill. They may forage at any time of day or night, perhaps most actively at dawn and dusk.

Its diet is mostly fish and other aquatic life. Eating fish (including catfish, eels, killifish, perch), frogs, tadpoles, aquatic insects, crayfish, crabs, salamanders and garter snakes. It has also been seen catching flying dragonflies. In drier habitats they may eat rodents, especially voles.

Its habitat is marshes and reedy lakes. They breed in freshwater marshes, mainly large, shallow wetlands with much tall marsh vegetation (cattails, grasses, sedges) and areas of open shallow water. This provides camouflage needed for protection from predators. They winter in similar areas, also in brackish coastal marshes on the southern coast or sometimes feed in dry grassy fields.

Their nesting site is usually in dense marsh growth above shallow water, sometimes on dry ground among dense grasses. The nest built by the female alone, is a platform of grasses, reeds, cattails, lined with fine grasses.

The male defends nesting territory by advertising his presence with his "booming" calls. Jed was able to get a movie of the Bittern doing his call. Watch it here:

Click here for the bigger version BitternCall 720p from Jed Schwartz on Vimeo.

Information found at: Audubon.org

May:

Picture found at allaboutbirds.org

Baltimore Orioles arriving in New Hampshire have completed a long journey from their winter homes in Central and South America. They arrive about the time that apple trees are blossoming. As the birds arrive, many people with backyard feeders know to put out orange halves along with their birdseed and suet offerings. In winter, orioles feed on blossom nectar and small fruits. When they reach New Hampshire in May, they're changing over to a summer diet that's mostly insect-based. Along with the usual bugs and caterpillars, they will eat pests such as fall webworms, tent caterpillars and gypsy moths.

Baltimore Orioles are more often heard than seen as they feed high in trees, searching leaves and small branches for insects, flowers, and fruit. You may also spot them lower down, plucking fruit from vines and bushes or sipping from hummingbird feeders. A strikingly beautiful bird, the adult males are flame-orange and black, with a solid-black head and one white bar on their black wings. Females and immature males are yellow-orange on the breast, grayish on the head and back, with two bold white wing bars. The Baltimore Oriole is one of the brightest birds in the forest.

Watch for the male’s slow, fluttering flights between tree tops and listen for their characteristic wink or chatter calls.

The Oriole nest is an engineering masterpiece! The female weaves a hanging-basket nest with plant fibers, grasses, vine and tree bark, 25-30 free above the ground. She then lays 4-6 speckled gray-blue eggs and incubates them for 11-14 days. Both parents feed the young chicks, who stay with their parents for two weeks after hatching.

Watch and listen for this beautiful and chatty bird, they will start to leave and go south by mid-summer.

Information found at: All About Birds and NHPTV.org

April:

Mountain Lion

The Eastern Cougar (mountain lion), one of 15 subspecies of cougar living in North America, was native to our area at the time of settlement. Also called puma, cougar, catamount and panther, the eastern cougar roamed the landscape preying primarily on deer for food. Elusive and not often seen even in colonial times, its existence was threatened by land clearing for agriculture and logging. The deforestation resulted in habitat changes affecting the availability of prey and cover for protection. In addition, fearful pioneers hunted mountain lions relentlessly, adding to their decline. By the late 1800's, the cougar population had been hunted and displaced out of existence east of the Mississippi.

However, throughout the many years since the large, tawny cat was officially declared extirpated from the region, reports continued to trickle in from individuals claiming to have seen one. Today, apparent sightings occur regularly. According to Mark Ellingwood, a wildlife biologist for the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, several dozen sightings are reported each year in New Hampshire. On the official record to date, there has not been any piece of hard evidence available that can positively confirm a single sighting. But those who claim to have seen one of the big cats are often quite passionate about their belief in what they saw or found.

If the reported sightings haven’t been substantiated by physical evidence and cougars aren’t here, what are people seeing that looks like a mountain lion? Some sightings have been determined to be a matter of mistaken identity, the creature later identified as a bobcat, housecat, or other animal. But in circumstances with good viewing conditions, it would seem difficult to not recognize the distinctive size, shape, color and cat-like movements of a mountain lion.

And if the great cats are indeed back, where did they come from? Are they holdouts from the original natives who have remained in Maine or the Canadian Maritime Provinces and have migrated back to our state?

As long as there are unconfirmed sightings, there will be a mountain lion mystery.

Information found at: Google - Mountain Lions in NH

March:

Fletcher & Family Sugar House, Picture by Jed Schwartz

It's Maple Syrup Time!

Each year, the New Hampshire maple industry produces close to 90,000 gallons of maple syrup. Maple sugaring time in New Hampshire runs from mid-February to mid-April.

As the frozen sap in the maple tree thaws, it begins to move and build up pressure within the tree. When the internal pressure reaches a certain point, sap will flow from any fresh wound in the tree. Freezing nights and warm sunny days create the pressure needed for a good sap Harvest.

In late February, New Hampshire maple producers tap their sugar maples by drilling a small hole in the trunk and inserting a spout. A bucket or plastic tubing is fastened to the spout and the crystal clear sap drips from the tree.

The sap is then collected and transported to the sugar house where it is boiled down in an evaporator over a blazing hot fire. As the steam rises from the evaporator pans, the sap becomes more concentrated until it finally reaches the proper density to be classified as syrup. It is then drawn from the evaporator, filtered, graded, and bottled. It takes approximately forty gallons of sap to make one gallon of pure maple syrup.

The maple sugaring season in New Hampshire usually lasts about six weeks from mid-February to mid-April, depending on the location and the weather.

Visit one of our local sugar houses to see sap being boiled, take a taste test and buy your supply of syrup for the year. Atkins Family Sugar House (Shawn & Kathy Atkins at 504 South Main St., Washington), Fletcher & Family Sugar House (Ed & Jane Thayer at 2528 E. Washington Rd. in East Washington), Crane's Sugar House (South Main Street in Washington), Chute's Sugar House (Lionel & Aileen Chute at Halfmoon Pond Road in Washington) and Hunt’s Sugar House (in Hillsboro Upper Village) are all open and ready for your visit.

Information found at: New Hampshire Maple Experience

February:

Porcupine's tree den

Porcupine's trail Pictures by Jed Schwartz

Porcupines in Winter

Jed found a porcupine's winter den at the base of a hollow tree out on his property. He peered in and Mr. Porcupine turned around and showed him his quills. They are solitary animals and live alone with not much social life.

During winter the porcupine does not hibernate but they sleep a lot and stay close to their dens. The porcupine does not usually move far and feeds within 100 meters of its den. During snow or rain it will remain in the den or, if outside feeding, it will sit hunched in a tree, even during subzero weather, until the rain or snow stops. When the weather is dry in winter it will feed at any time of the day or night, but during the rest of the year it is nocturnal despite the weather. In mountainous country, the porcupines will often descend during the winter along well-defined routes marked by debarked trees.

The porcupine feeds largely on the inner bark of trees in winter, but it will also feed on a variety of other plants. During winter, although the needles and bark of most trees are acceptable, there are clear favorites: yellow pine in the west, white pine in the Great Lakes area, and hemlock in the northeast states. When the sap rises in spring, the bark of maples is favored along with the catkins and leaves of alder, poplar, and willow.

When in a den or up a tree, a porcupine is not always easy to see, but noisy chewing, cut twigs, and missing patches of bark may advertise its presence. Around feeding trees and especially outside the winter dens, scats, or droppings, are often visible (see picture above). In winter, their tracks can be recognized by the firm print of the whole sole placed heavily on the ground, the long claw marks, and, sometimes, marks where the tail has dragged. If the snow is soft and deep, the porcupine trail becomes more of a deep trough through the snow.

Information found at: Hinterland Who's Who

To view yearly archives of our "New In

Nature" series click on year you wish to see.

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

|