|

Do you have something

happening in your corner of Washington? - Please call a member

or e-mail your observations to have them included here

November:

Purple Finch picture from Wikicommons

We have been talking about song birds and

wondered about how the changing habitat and climate is effecting

them.

Climate change is a large event that has

been widely discussed and most people know the consequences

of it - rising sea levels, more frequent and severe weather

events, drought, extinctions, the spread of disease. But most

people don't think about the smaller changes that warming

brings and their effects on our local plants and wildlife.

New Hampshire is home to an incredible

diversity of native wildlife species, including 283 birds,

64 mammals, 50 fish, 19 reptiles and 21 amphibians. Rising

temperatures and sea level in the state will likely change

the makeup of entire ecosystems, forcing wildlife to shift

their ranges or adapt.

Already, there are signs that birdlife

is responding to climate change. Warming may affect songbirds'

habitat. Because native forests are adapted to local climates,

many trees acclimated to cool environments are likely to shift

northward. In New England, for example, southern oaks and

hickories may replace today’s mix of maple, birch and beech

trees.

Warming also has had a measurable impact on the timing

of such seasonal events as migration and breeding. The downside

of early migration and reproduction, of course, is that a

species’ breeding cycle could get out of sync with its food

supply.

Early birds beware: Breed too soon, and the worms

needed to feed hungry hatchlings may be nowhere to be found.

Yet such loss of synchronization with food sources is exactly

what many scientists fear will happen more frequently as birds

migrate and breed earlier in the year in response to warming

climate. Even with only moderate warming, some species are

already arriving at breeding territories before food is available

for their offspring. For birds, the most devastating consequence

of global warming would be loss of entire habitats on which

species depend.

Many birds are linked to specific vegetation—and

it could take decades or centuries for plants to respond to

global warming. Birds requiring a mature pine forest, may

find that their habitat is already scarce. If the species

has to shift its range northward to stay in a cooler environment

will it be able to adapt and use other trees?

If an ecosystem,

in turn, loses a bird that helps control insect pests, the

results could be catastrophic, for humans as well as other

species. In the boreal forests of eastern North America, for

instance, nesting wood warblers are important predators of

the eastern spruce budworm, which defoliates millions of acres

of timberland every year. Without the birds, those losses

would likely be far greater. Under normal conditions, warblers

consume up to 84 percent of the budworm’s larvae and pupae.

We are already seeing some signs of these changes in our monthly

observations of local wildlife. While it is fun to see birds

that aren't normally seen around here, if things continue

this way, our state bird, the purple finch could vanish from

New Hampshire.

Information from National

Wildlife Federation

What are 10 climate saving actions I can take?

Clean Air Cool Planet

October:

Frog picture from Herpetology Photos

As the ponds freeze and winter comes on, we wondered how frogs

survive, where do they go and what do they do all winter?

Hibernation is a common response to the cold winter of temperate climates.

After an animal finds or makes a living space (hibernaculum) that protects it from winter

weather and predators, the animal's metabolism slows dramatically, so it can "sleep away"

the winter by utilizing its body's energy stores. When spring weather arrives, the animal

"wakes up" and leaves its hibernaculum to get on with the business of feeding and breeding.

Aquatic frogs such as the leopard frog and American bullfrog

typically hibernate underwater. A common misconception is

that they spend the winter the way aquatic turtles do, dug

into the mud at the bottom of a pond or stream. In fact, hibernating

frogs would suffocate if they dug into the mud for an extended

period of time. A hibernating turtle's metabolism slows down

so drastically that it can get by on the mud's meager oxygen

supply. Hibernating aquatic frogs, however, must be near oxygen-rich

water and spend a good portion of the winter just lying on

top of the mud or only partially buried. They may even slowly

swim around from time to time.

Terrestrial frogs normally hibernate on land. American toads

and other frogs that are good diggers burrow deep into the

soil, safely below the frost line. Some frogs, such as the

wood frog and the spring peeper, are not adept at digging

and instead seek out deep cracks and crevices in logs or rocks,

or just dig down as far as they can in the leaf litter. These

hibernacula are not as well protected from frigid weather

and may freeze, along with their inhabitants.

And yet the frogs do not die. Why? Antifreeze!

True enough, ice crystals form in such places as the body

cavity and bladder and under the skin, but a high concentration

of glucose in the frog's vital organs prevents freezing. A

partially frozen frog will stop breathing, and its heart will

stop beating. It will appear quite dead. But when the hibernaculum

warms up above freezing, the frog's frozen portions will thaw,

and its heart and lungs resume activity--there really is such

a thing as the living dead!

Information from Scientific American

September:

Goose picture from UVM

Keep your eyes on the skies during the next couple of weeks for the high-flying Canada goose migration.

In a learned family tradition, all the geese hatched in certain areas travel to the same winter destination.

Two different populations of migrating geese pass over the Granite State.

One group, called the Atlantic population, travels down the Connecticut River Valley as they wing their

way south from spring breeding grounds in the Hudson and James bays in Canada to their winter home in the Chesapeake Bay.

The Atlantic population, with about 175,000 breeding pairs, is doing very well,

according to Fish and Game Wildlife Biologist Ed Robinson, who predicts a larger fall flight this year than last.

The second population of migrating geese is called the North Atlantic population, with about 197,000 breeding and

non-breeding birds. More of a coastal species, these geese breed during the spring in Labrador in the Maritime

Provinces of Canada, and winter in New Hampshire's Great Bay, as well as in coastal Massachusetts and Connecticut.

This population is also flourishing, and an increased number of birds is expected this year.

New Hampshire has still another group of Canada geese - a resident population of about 30,000 birds.

Though the same species, this population does not migrate. Our resident Canada geese are more productive

than the migrating populations, so can be harvested at different rates by hunters. The resident Canada goose

hunting season, with a higher bag limit than the open season, ended on September 25, before the big surges

of migrants started coming through the state.

Information from NH Fish and Game

August:

pictures from Loon

Preservation Committee

Loons!

In Washington we are very lucky to have loons nesting on several of our lakes.

They face many challenges for their survival and are on the threatened wildlife list in NH.

Ken told us about two very dramatic reports of a Bald Eagle

attack on a loon chick on Millen Pond. He said the eagle dive-bombed

the chick three times, but luckily it never did get it. The

loon parents were nearby desperately trying to distract the

eagle and he guessed that it helped, as the eagle was not

successful and the chick survived the attack. Island Pond

is also fortunate to have a nesting pair of loons with 2 chicks.

Loons spend their days feeding, preening, resting, and caring for their young.

Their diet in summer consists primarily of fish, and loons eat mostly perch,

suckers, catfish, sunfish, smelt, and minnows. They will also eat crayfish,

frogs, leeches, and snails.

They build their nests close to the water, often on a small

island, muskrat house, half-submerged log, or sedge mat. The

same sites are often used from year to year. Loons will use

mud, grass, moss, pine needles and/or clumps of mud and vegetation

collected from the lake bottom to build a nest. Both the male

and female help with nest building.

Usually one or two eggs are laid in late May or June, and incubation of the eggs

generally lasts 26-28 days. Loon chicks covered in brown-black down appear on

the water in late June or July. Chicks can swim right away, but spend time

riding on their parents' backs to rest, conserve heat, and avoid predators

such as large fish, snapping turtles, gulls and eagles. After their first

day or two of life, the chicks do not return to the nest.

Chicks are fed small food items including minnows, insects and crayfish

caught by their parents for the first few weeks of life, and up until

eight weeks of age, the adults are with them most of the time. Gradually,

the chicks begin to dive for some of their own food, and by 12 weeks of age,

the chicks are providing almost all of their own food and are able to fly.

There are many dangers for loons and their chicks on our lakes.

Swallowing a single lead sinker or jig can kill a loon or

other waterbird. Loon chicks can be killed by an older sibling,

or by an intruding adult loon or other predators. The largest

single source of human-caused chick mortality is from collisions

with fast-moving boats and personal watercraft.

Loon nests fail for a variety of reasons. The close approach

of people can cause incubating loons to flush from the nest,

sometimes resulting in loss of eggs to scavenger birds and

mammals. Please keep your distance if you know loons are nesting

or living on your lake.

Development and recreational pressures on lakes have been implicated in declines

in numbers of breeding loons and in reduced loon breeding success. Several

researchers suggest that shoreline development and associated recreational

use of lakes play an important role in limiting loon populations, and might

be the primary factors in the reduction of the loon's historical breeding range.

The Loon Preservation Committee (LPC) was created in New Hampshire,

in 1975, in response to concerns about a dramatically declining

loon population and the effects of human activities on loons.

LPC’s mission is to restore and maintain a healthy population

of loons throughout New Hampshire; to monitor the health and

productivity of loon populations as sentinels of environmental

quality; and to promote a greater understanding of loons and

the larger natural world. 34 years later they are still at

work around our state.

The Loon Preservation Committee was one of the first organizations anywhere

to show that coordinated and thoughtful human actions could reverse the decline

of a threatened or endangered species.

For more information about loons,

to learn about the LPC's important work with loons, to read

their newsletter or join their organization go here: Loon

Preservation Committee

July:

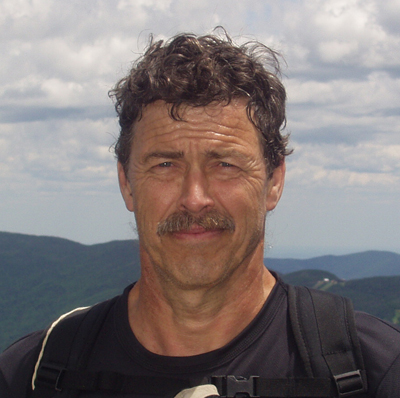

picture from Lynn Cook

A Tribute to Rich Cook

The Washington Conservation Commission bids a tearful goodbye

to our friend and long time commission member Rich Cook. He

passed away on July 16th following an accident and a valiant

fight to recover from his injuries.

Rich was a true conservationist who loved farming, the natural

world, and all things Washington.

He spent his working years as a Merchant Marine sailing the

world's oceans, serving much of his career as Captain. Though

he visited ports all over the world he always delighted in

returning to his farm in East Washington. Bifrost Farm was

his sanctuary and there he and Lynn and their children raised

and trained Morgan horses, grew organic Shiitaki mushrooms,

kept chickens for eggs and meat and cultivated bountiful vegetable

gardens and berries. He had a deep interest in sustainable

farming and locally raised food.

Rich took great interest in nature and spent a lot of time

in the great outdoors. He cut his own wood and enjoyed hiking

and riding horses. He also loved spending time on the water

sailing and kayaking. Rich had an innate sense of curiosity

about the natural world and the environment and read constantly

to enrich his knowledge.

He joined the Conservation Commission as a member right at

the start and continued on as an ex-officio member after he

was elected to the town's Board of Selectmen. Through the

years, he worked with us on land protection and preservation

projects, watershed restoration and was always willing to

help do whatever needed to be done, including picking up trash

along our highway route and sloshing around in the vernal

pool. He always made it fun and interesting no matter what

we were doing.

He loved the land and his community and gave huge amounts

of his time to both. He had a wonderful and wry sense of humor

and always had great observations and stories to tell. Rich

lived his life doing what he loved and felt passionately about.

His legacy will live on through his children and Lynn and

we will carry on, in his absence, to do the important conservation

work in Washington that we all shared.

We will all miss him terribly but we are all a great deal

richer for having known him. He was truly a "force of nature"

and now, he is a "force in nature". Look for him in the mountains,

in your garden, the beaver bog, or the local pond. He's still

here with us.

June:

picture from

Duncraft

Have you seen any bats this summer?

In New Hampshire bats are the primary control agents for nocturnal

insect pests a little brown bat can eat over half its body

weight in one night. Because of their high metabolism, bats

also play a role in recycling nutrients through an ecosystem.

New Hampshire is home to eight species of insect-eating bats.

During the summer months, particularly June and July, bats

can be found throughout the state in virtually every habitat.

At night, they can often be seen foraging over waterbodies,

traveling along wooded paths or hunting around street lamps.

During the day, they roost in a large variety of places, including

under tree bark, in rock and tree crevices and in human structures

and barns.

Winter surveys by biologists show that the deadly bat disease

called White Nose Syndrome (WNS) is having

a dramatic impact on New Hampshire's bat populations. Currently,

five of the eight species of New Hampshire bats are affected

by WNS, including the common little brown bat. One species,

the northern long-eared bat, has now disappeared from many

hibernacula (bat wintering places) throughout the Northeast.

WNS first appeared in New York in 2006 and now has been documented

in 11 states; it has expanded as far south as Tennessee and

as far north as Ontario, Canada. Some of the spread can be

attributed to migrating bats, but it is also feared that humans

are transporting the fungus on their caving clothing and gear.

Because of this, the US Fish & Wildlife Service requests all

cavers to disinfect their gear between cave visits. In addition,

do not bring any gear used in an infected state into a cave

in an uninfected state, as disinfection procedures are not

100% effective, and respect all cave closures.

Why is the spread of WNS so important? Bats are the biggest

predator of night-flying insects. Also, recovery from the

onslaught of the disease will be difficult, because bats are

slow breeders. They typically live a long life (over 20 years)

and produce one, or rarely two, pups each year. As with most

young of the year wildlife, not all pups survive, so rebuilding

bat populations after such a rapid decline could take decades.

Hundreds of scientists across the country are working to solve

the mysteries of WNS. We know that the fungus is persistent

it remains in a cave and can infect bats that return there.

Two types of treatments designed to control the fungus on

the bats have been tested, but the results are not yet in.

How can you help? If you have bats in your

barn or house or other buildings, please try to leave them

there, say biologists. Bats breed much more successfully

in large colonies where the combined heat helps the young

bats grow. If you have problems with guano, put a layer of

plastic between the bats and your equipment, but DO NOT seal

the bats in. Also, stay out of caves and mines, year round.

The fungus can be picked up on clothing and gear, and transported

to other sites.

NH Fish and Game would like help this summer counting bats

in your neighborhood, for more information on joining this

worthwhile research project click here: NH

Fish and Game Bat Count

Please help. If you don't have time to count for the state

but you have seen bats, send us an email and let us know where

and when, wcc@washingtonnh.org

Thanks!

This information and more can

be found at: NH

Fish and Game

and NH

Wildlife Journal

May:

Hognose Snake - pictures from

Arin Mills

Conservation Commission member Arin Mills

works for the NH National Guard as a Conservation Specialist

and she has been tracking an Eastern Hognose Snake

using radio telemetry on one of their properties.

The Eastern Hognose Snake has a thick body, a wide neck, and

a slightly upturned snout and can grow to nearly four feet

long. The color of this snake can vary with yellow, tan, brown

to red and orange with light and dark blotches. There is also

a dark phase in which the body is almost uniform grayish-black

color. It can be confused with the Garter Snake or Timber

Rattlesnake.

They require sandy, gravely soils found in open fields, river

valleys, pine forests, and upland hillsides and live in woods

or fields.

They feed predominately on toads (their favorite meal) and

therefore need breeding habitat (e.g., wetlands, vernal pools)

for amphibians. They will also eat frogs, small mammals, birds,

bird eggs, insects, lizards, smaller snakes, reptile eggs,

and carrion (dead animals).

During June or July the female Hognose lays around 60 eggs

a few inches underground or under woody debris and the eggs

hatch 1 1/2 to 2 months later. In Winter, Hognose snakes hibernate

by burrowing into the soil, or by making a den out of an old

woodchuck, skunk, or fox burrow.

If disturbed by a predator, these snakes have several interesting

ways to defend themselves. First, they will inflate their

necks to look bigger, and they will hiss loudly and strike.

When they do this, they very much resemble cobras. If looking

tough doesn't work, the Eastern Hognose Snake will play dead

and they are very good at it. The snake will roll over and

open its mouth with its tongue hanging out. They will even

stay limp when they are picked up. If you place it right side

up, the snake will flop right back over and play dead. If

this doesn't work, the snake may bite; however, hognose snakes

rarely bite people.

The state ranks this snake as endangered so please let them

know if you see one! Report all sightings of this snake to

NH Fish and Game at 603-271-2461 or

RAARP@wildlife.nh.gov - Photographs are encouraged.

Information from: NH

Fish and Game and Fairfax

County Public Schools Ecology Study

April:

Baby Black Bear at the birdfeeder

- picture from June Manning

Time to take down your bird feeders!

This little guy is cute but his Mom isn't far away and can

do lots of damage to your feeder and property.

"Late March is the time when we typically start seeing

bear activity in New Hampshire. To prevent attracting

a bear to your residence, it is essential that bird feeders

are taken down and put away until next winter," says Andy

Timmins, Bear Project Leader for New Hampshire Fish and Game.

"This isn't about bird feeders, it's about the safety and

wellbeing of black bears. Bears that frequent homes for easy

pickings often have a shorter life expectancy than bears that

don't." Take down your feeders and save a bear.

"Given that sunflower seed is more nutritious than most foods

a bear will find in the woods, it is easy to understand why

some residences get visited by bears every spring," Timmins

added. "Don't be fooled by the fact that several inches of

snow still cover the ground across much of the state; snow

depth has little influence on when bears decide to emerge

from winter dens."

During the denning period, bears typically lose 25% of their

body weight, and a lactating female with newborn cubs may

lose as much as 40%. Post-denning bears are readily attracted

to human related foods. The statewide black bear population

is considered relatively stable -- thanks to careful management

by Fish and Game -- and currently is about 4,800 bears.

Here are a few tips for safety:

Finish your bird feeding activities by April 1 each year.

Don't begin feeding the birds again prior to December 1 or

the onset of prolonged winter weather (the birds will do just

fine). Bears are clever and coupled with their strength and

agility, this makes it very difficult to establish bear-proof

bird feeders. Encourage your bird-feeding friends and neighbors

to adhere to these guidelines. Never intentionally feed bears!

A black bear's presence in a residential area may create fear

among neighbors and lead to negative consequences for the

bear. Regardless of the dates specified above, if a bear

is active in your community, you should cease and desist all

bird feeding activity. Bears that have access to winter

feeders will sometimes remain active, visiting the feeder

late into December, and periodically, beyond.

Information from:NH

Fish and Game

and: NH

Fish and Game Bears

March:

Usnea picture from Wikipedia

While walking near the Bradford Bog, Jed

and Nan found a strange gray/green hairy plant (?) growing

on some tree branches. They wondered what it was and it turned

out to be Usnea.

Usnea is the generic and scientific name for several species

of lichen that generally grow hanging from tree branches,

resembling grey or greenish hair. It is sometimes referred

to commonly as Old Man's Beard, Beard Lichen, or Treemoss.

Usnea looks very similar to Spanish Moss, so much so that

the latter plant's Latin name is derived from it. Usnea grows

all over the world and like other lichens it is a symbiosis

of a fungus and an alga.

Usnea has several unique characteristics which make its identification

easy if stranded in the wilderness far from a hospital. Usnea

lichens can be easily identified by pulling back the outer

sheath on the main stem. Usnea lichens have an elastic pure

white chord running through the center of the main stem. Lichen

species which resemble Usnea do not have this white cord,

and appear grey-green throughout.

Usnea lichen is important to note because it has life-saving

potential. Usnea has been used medicinally for at least 1000

years. Usnic Acid (C18H16O7), a potent antibiotic and antifungal

agent, is found in most species. This, combined with the hairlike

structure of the lichen, means that historically Usnea lent

itself well to treating surface wounds when sterile gauze

and modern antibiotics were unavailable. It is also edible

and high in vitamin C. Native Americans employed it as a compress

on severe battle wounds to prevent infection and gangrene,

and it was also taken internally to fight infections. Usnea

contains potent antibiotics which can halt infection and are

broad spectrum and effective against all gram-positive and

tuberculosis bacterial species.

In modern American herbal medicine, Usnea is primarily used

in lung and upper respiratory tract infections, and urinary

tract infections. There are no human clinical trials to either

support or refute either practice, although in vitro research

does strongly support Usnea's antimicrobial properties.

Information about Usnea

found here : Wikipedia

February:

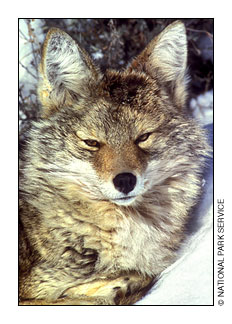

Coyote picture from National

Park Service

Coyotes!

Carol heard coyotes howling recently and they sounded close.

We wondered about the coyotes in this area and here is what

we found out.

New Hampshire's coyotes are eastern coyotes and they typically

weigh 30-50 pounds, are 48-60 inches long, approximately twice

the size of their close relative, the western coyote. Eastern

coyotes have long legs, thick fur, a pointy snout, a drooping

bushy black-tipped tail and range in color from a silvery

gray to a grizzled, brownish red. The average life span of

a wild coyote is four years. Though coyotes are often mistaken

for a domestic dog hybrid, recent genetic research has attributed

the eastern coyote's larger size and unique behavioral characteristics

to interbreeding with Canadian gray wolves. Unlike the wolf

or domestic dog, coyotes run with their tail pointing down.

Although the historical evidence supporting occurrence of

coyotes in New England is inconclusive, no coyotes were present

in the late 1800s. The first verified account of a coyote

in New Hampshire was in Grafton County in 1944. Between 1972

and 1980 coyotes spread across N.H. from Colebrook to Seabrook.

Today, coyotes are common in every county throughout the state.

Coyotes are generalists, eating whatever food is seasonally

abundant. Coyotes are known to feed on mice, squirrels, woodchucks,

snowshoe hare, fawns, house cats, carrion, amphibians, garbage,

insects and fruit. Coyotes utilize forested habitats, shrubby

open fields, marshy areas and river valleys.

The Eastern coyote is a social animal that generally selects

a lifelong mate. Coyotes are quite vocal during their January

to March breeding season. Both parents care for their young,

occasionally with the assistance of older offspring. Four

to eight pups are born in early May.

Within a year some pups will disperse long distances to find

their own territories, while other offspring may remain with

their parents and form a small pack.

Territories range in size from 5-25 square miles and are usually

shared by a mated pair and occasionally their offspring. Coyotes

are capable of many distinct vocalizations - the yipping of

youngsters, barks to indicate a threat, long howls used to

bring pack members together, and group yip-howls issued when

pack members reunite.

Coyotes are elusive, adaptive, intelligent animals that manage

to hold their own when living in close contact with humans.

Most coyote management attempts have been designed to reduce

their population numbers, however, due to their fertility,

behavior and adaptability, those attempts have failed.

The great majority of coyotes don't prey upon livestock. However,

once a coyote learns that young livestock are easy prey, depredation

can become a problem. If this occurs, removal of the offending

coyote is often recommended. However, when farms are situated

in a coyote territory with no depredation, the resident coyote

may actually be an asset to the farm by removing rodents and

preventing problem coyotes from moving into the area. In suburban

areas coyotes have been known to kill house cats. Keeping

your pets and pet food inside at night helps reduce the likelihood

that a family pet will become prey. Coyotes pose little risk

to people and in New Hampshire there has never been a report

of a coyote attacking a person.

Information about coyotes found

here : NH

Fish and Game

January:

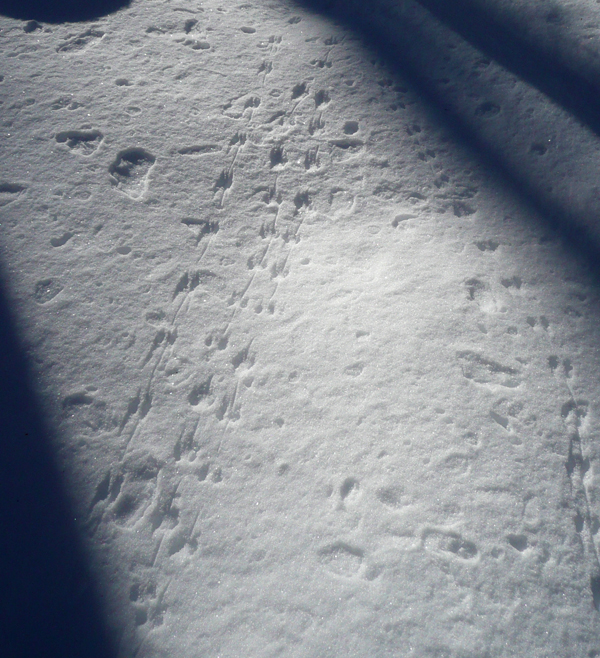

Moose tracks and scat - photos

by Jed Schwartz

Animal tracks in the snow!

Both Sandy and Jed said they have been out enjoying all the

fresh snow cover on XC skis and snow shoes. They each commented

on having lots of fun looking at and trying to identify all

the varied tracks animals leave in the snow. It's a great

time to get out in the snow and have fun tracking animals!

This time of year you can easily see the comings and goings

(and sometimes doings!) of all the animals in our forests

and fields.

Rabbit tracks

Small mammal tracks

The best time to study animal tracks is in the morning, before

the ground becomes disrupted. Keep in mind the quality of

the tracks will depend on the texture and depth of the snow.

Thus, a crisp early-morning snow will provide for better tracking,

while late-afternoon prints might have turned to slush after

a day of sun. Snow that is too deep will not leave a clear

cut print.

Weasel (?) tracks

Note the location of the tracks as this might help determine

the type of animal that made them. For instance, an otter

will be more likely to make tracks near water. Pay particular

attention to the number of toes, track size, shape and the

presence or absence of claws. Remember that track sizes will

vary according to gender and age. Be on the lookout for gnawed

twigs, tree scrapings and animal droppings, known as scat.

Deer tracks

Coyote

tracks and scat

The best time to study animal tracks is in the morning, before

Animal tracks are classified into many categories based on

individual characteristics.

• Rodents have four front and five back toes with claws.

Animals such as squirrels, rats, chipmunks, porcupines, beavers

and groundhogs are in this category.

• Rabbits have four front and four back toes with the

back feet measuring two times larger than the front.

• The cat family has four front and four back toes,

with claws rarely visible as cats have retractable claws.

Cats' front feet are about a half size larger than the back

feet. House cats, mountain lions, bobcats and the lynx are

members of this group.

• The dog family has four front and four back toes with

claws. The front feet are a third larger than the back feet.

Domestic dogs, foxes, wolves and coyotes are in this category.

• Weasels have five front and five back toes with claws.

Minks, otters, wolverines and badgers are classified in the

weasel family. In most cases, the weasel track will only leave

an impression of four toes.

• Deer have two toes in front and two in the back, with

the front feet about a half size larger than the back feet.

Moose are similar but much larger size with a longer stride.

• Bear, raccoon, opossum and skunk leave human looking-shaped

tracks with five front and five rear toes with claws.

• Wild Turkeys leave a large three toed track. Other large

birds (grouse, crows) are also three toed, crows have a fourth

opposing toe.

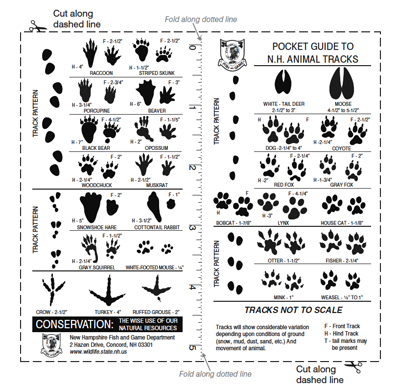

A great tracking card like the one pictured above is available

from NH Fish and Game (see link below) and can help you identify

the tracks you see. Let us know what animal tracks you find

out in your corner of Washington.

Tracking Card is available here

: NH

Fish and Game

Information about identifying

animal tracks was found here: ehow.com

To view yearly archives of our "New In

Nature" series click on year you wish to see.

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

|