|

Do you have something

happening in your corner of Washington? - Please call a member

or e-mail your observations to have them included here

December 2003:

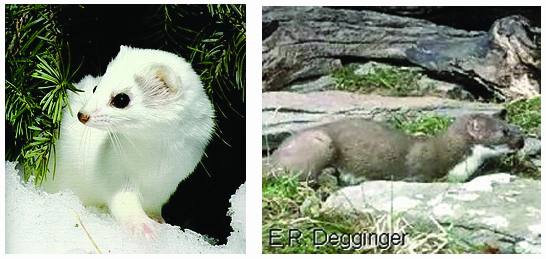

Carol writes: I just saw a beautiful

weasel scurrying along the rocks on the shore of

Halfmoon Pond. Hereís what Fish and Game has to say about

weasels:

Getting ready for winter for some

creatures involves more than just finding the right kind of

food and shelter. For snowshoe hare and several members of

the weasel family, it also means changing their summer brown

coat to a winter white one. New Hampshire has two species

of weasels that change their coat color -- the long-tailed

weasel and the ermine, or short-tailed weasel. In mid-October,

both species begin to lose their reddish-brown coats and usually

by mid-November they are all white.

Only the tips of their tails remain black.

In March, they start to lose their white coats and change

back to their reddish-brown summer color. The differences

between the two weasel species are slight. Their tracks give

us the best clue as to which one we are seeing. Weasels leave

behind a "2-2" track pattern. The front feet come down and,

as the front feet leave the ground, the hind feet come in

immediately behind. This type of movement is called bounding.

An ermine track looks like short strides alternating with

long strides, with an occasional drag made between the tracks.

The trail width is a little over an inch and the stride ranges

from 9 to 30 inches. The long-tailed weasel's track is slightly

larger. Ermine are 7 to 13 inches long (without the tail)

and weigh 2 to 7 ounces, about as heavy as an average banana.

Male ermines are larger than females. This can make it difficult

to identify tracks, as a larger male ermine may be as big

as a small long-tailed weasel. Ermine tend to frequent areas

where there is possible prey, like woodpiles, brushpiles and

stone walls. Common foods include mice, chipmunks, voles,

shrews and rabbits. In the summer, they also eat frogs, small

snakes, birds, insects and earthworms. The size of their home

range depends on prey availability. Males have larger home

ranges and regularly make a circuit seeking food. Females

have smaller home ranges of from 5 to 24 acres and hunt with

trails radiating out from their den site. In the winter, female

ermines often hunt subnivean (under the snow), using the tunnels

made by their prey. Ermines can squeeze into tunnels less

than an inch in diameter! When temperatures are low and they

need additional thermal protection, ermines often will rest

in the tunnels and nests of their prey. If there is plenty

of food, ermine may eat the internal organs, brains and muscles

and leave the rest of their prey. So, a pile of mouse carcasses

with the heads missing or the remains of just legs and tails

are signs of ermine activity. They kill instantly by biting

their prey at the base of the neck. In addition, ermine will

cache (store) foods, so they can return to eat more. -

Judy Silverberg, wildlife educator

Last Big Social

Event for Moose: As the

leaves fall off the trees and temperatures drop, moose begin

to think about their weight. The rut is nearly over and winter

is fast approaching. During the rut, food was not a first

priority for the bulls. They were far more interested in courting

as many cows as they could find, and they traveled far and

wide to find them. As a result, they lost quite a bit of weight.

While this sounds like a great weight loss plan -- one many

of us could probably follow successfully! -- it has serious

repercussions for the moose. In order to successfully survive

the cold and poor food resources of the coming winter, moose

must have good fat reserves. To enter the winter as a "lean

mean fighting machine" is tantamount to a death sentence.

So, in mid-October and November, thoughts of romance are set

aside and serious feeding begins. At this time of year, moose

will visit any area that provides good forage. It's not unusual

to walk into a prime clear-cut and find multiple bulls of

various ages, along with a number of cows, feeding together.

Moose will consume up to 40 pounds of leaves, buds and the

new woody growth of young deciduous trees each day. During

the oncoming winter, the only food available will be buds

and twigs, which are low in nutritional value. Moose movements

will be restricted by crust and deep snow, further impacting

their ability to get to available foods. Moose have adapted

to this regimen, and, as winter settles in, their metabolism

and appetite will slow down. They'll rely on the stored fat

supplies within their bodies and slowed metabolism to get

them through the winter. Regardless of how much food is available,

moose will eat and move around less in an effort to conserve

energy, in effect protecting their all-important fat deposits.

So, for the next few weeks, don't be surprised if you see

multiple moose together feeding in a clear-cut or any area

that provides an abundance of deciduous browse. These groups

won't stay together; they will go their separate ways each

evening and eventually part for the winter. Cows will keep

their calves and, occasionally, their yearlings with them,

and bulls may pair up for the winter. But until spring, this

is the last big "social event" for moose and definitely the

last good feed. - Kristine

Bontaites, moose project leader

If you would like to sign up for

Fish and Gameís Wildlife Journal email list:

http://www.wildlife.state.nh.us/Inside_FandG/join_mail_list.htm

The Future of Food

in New England: report from the citizen panel http://www.sustainableunh.unh.edu/fas/justfoods/Future_of_Food.pdf

October 2003:

Monarch Butterflies (Dan

aus plexippus) are migrating! They travel up to three-thousand

miles twice a year: south in the fall and north in the spring.

To avoid the long, cold northern winters, monarchs west of

the Rocky Mountains winter along the California coast. Those

east of the Rockies fly south to the mountain forests of Mexico.

Unlike migrating birds and whales, however, individual monarchs

only make the round-trip once. It is their great-grandchildren

that return south the following fall. Eastern populations

winter in Florida, along the coast of Texas, and in Mexico,

and return to the north in spring. Monarch butterflies follow

the same migration patterns every year. Tens of millions of

these butterflies spend the winter in a mountain forest in

Central Mexico.

September 2003:

Mushrooms are everywhere!

With our wet, late summer weather there are many mushrooms

to see. Grab your mushroom guide and go exploring for the

many varieties found in our area. A good beginnerís guide

to mushrooms is the National Audubon Society Field Guide to

Mushrooms of North America.

Carol brought in a "Maitakei" also known as "Hen-of-

the-woods" weighing in at 9 lbs. These mushrooms grow

at the base of really large old oak trees. They are an edible

mushroom, and are used medicinally for conditions such as

cancer, high blood pressure and diabetes. These mushrooms

can grow up to 100 lbs. The Japanese call this the dancing

mushroom. It used to be that they could trade this mushroom

pound for pound with silver, so they certainly did a little

dance when they found it. The mushrooms that we collect and

eat are merely the fruiting bodies of an organism that lives

underground or in wood. It doesnít hurt the organism to pick

the fruiting body.

Hen-of-the-Woods (Grifola frondosa)

Description: This mushroom really does

look something like a large, ruffled chicken. It grows as

a bouquet of grayish-brown, fan-shaped, overlapping caps,

with offcenter white talks branching from a single thick base.

On the underside, the pore surface is white. It often grows

in the same spot year after year.

When and Where: Summer and fall; on the ground at the base

of trees, or on stumps.

Cautions: Many gilled mushrooms grow in large clumps- remember

that hen-of-the-woods is a pore fungus. This mushroom has

no poisonous look-alikes, but there are some similar species

of pore fungi that are tough and inedible. If what you have

tastes leathery or otherwise unpleasant, you probably didn't

pick a hen-of-the-woods.

Cooking Hints: Use only fresh, tender portions. Simmer in

salted water until tender (requires long, slow cooking), and

serve as a vegetable with cream sauce; or chill after cooking

and use on salads.

Moose visit! Pamela Russo writes - "I was

spending the weekend at a friend's home on Ashuelot Pond in

Washington. I was out on the back deck very early in the morning

(6:45 a.m. on 9/21/03) thinking what a great picture I could

get of the sun coming up on the lake when this little guy

walked through the back yard."

Lots of reports of moose in Ashuelot.

A bald eagle has been visiting the upper Ashuelot.

There seem to be more coyote around than the past couple years.

June 2003:

The Loons are back in

Washington

John Tweedy had a bear at his house last

night (8:44 p.m.)

Carol Andrews reported that the rhodora are

blooming in the Bradford Bog

Don Richard saw a salamander the size of

a spotted, but with no spots

May 2003:

Salamanders are moving

to vernal pools

Mayflowers (trailing arbutus) are in bloom

Listen for woodcock in open fields of about

2 acres or larger, preferably next to a wetland. Listen for

their distinctive "peent" call and watch for their

spectacular mating displays at dusk.

Black flies are coming! The bad news: Approximately

40 species of black flies are known to occur in New Hampshire.

The good news: Of these species, only 4 or 5 are considered

to be significant human biters or annoying.

April 2003:

Spotted Salamanders will

be moving soon. Watch for them on roads, especially on rainy

nights. Get out to see activity in vernal pools.

Suggested Reading: A Field Guide to the animals of Vernal

Pools, by Leo P. Kenney and Matthew R. Burne.

Let's Talk Turkey: The Seabrook nuclear plant

in New Hampshire was locked down Friday (3/21?) after a "potential

intruder" was spotted on a security screen. "Immediately,

we locked down the plant.... We called on the sea coast security,

the New Hampshire State police and the local Seabrook police,"

a plant spokesman said. A security worker, however, told the

FBI he saw "a large bird (probably a wild turkey) with approximately

a 4-foot wingspan fly across the road in front of him" while

he was patrolling the area. In its report to the NRC, Seabrook

noted the turkey sighting "coincided with the location and

time the security operator saw the image on his screen." The

NRC called off the alarm.

Ashuelot River Local Advisory Committee Report on their hike

on 3/15 "Today, several members of the Ashuelot River Local

Advisory Committee and their spouses hiked on snowshoes down

the middle of the Ashuelot River from Mountain Road to the

beginning of Ashuelot Pond. It was so-o-o- beautiful!† And

we saw tracks of otter, beaver, fisher, red fox, gray fox,

snowshoe hare, and mink. Additionally, we saw many bear bites

on balsam firs along the edge of the river. There were also

a few deer rubs (no tracks) and a moose sign. It is an untrammeled

part of the river. The open expanses are lovely, including

a vast marshy area (frozen over now) near the Washington-Lempster

line. There was one house where we began and houses at the

end (as well as noisy snowmobiles on the pond). Otherwise,

all quiet except for the yapping of beagles released to help

hare hunters."† Ann Sweet

(Sullivan)

March 2003:

10' 5.5" of snow so far this winter!

This is the season to hear Owls!

Who's Who in the Owl Family

Owls are much more numerous than people realize. Unless you

live deep in a treeless city, there is likely to be an owl

within walking distance of your house. This is the time of

year when it's easier to find them. A cold night in midwinter

is a good time to locate owls as they call to each other during

their breeding season. Eleven species of owl occur in New

Hampshire. The most common species live in forests, swamps,

woodlots, farms and even suburban yards. None of these owls

are easy to see by day; they spend most of the daylight hours

hidden in tree cavities or perched in thick vegetation. Their

plumage color and pattern is designed to blend in and their

nocturnal activity period makes them difficult to detect.

Owls see and hear what humans cannot. Many special adaptations

combine to make owls superb nocturnal predators. Owls can

see 35 to 100 times better in dim light than we can. Their

eyes are fixed in their sockets. The only way they can move

their eyes is rotating their head. Their large, sensitive

ears, located to the outside of their large eyes enable them

to locate distance and direction of sound with amazing accuracy.

Here is a little bit about the four most common owls found

in New Hampshire.

Saw-whet Owl

At 7-8 inches high, the saw-whet owl is the smallest of the

owls found in New Hampshire. Though this owl does give a rasp

call like the sound of a saw being sharpened, its most common

call is "too-too-too." It can repeat this call more than 100

times per minute. It is most likely to be found perched in

or near a dense stand of evergreens like hemlock or spruce,

and feeds primarily on rodents.

Barred Owl

"Who Cooks for you? Who cooks for you,

all?" is the call of the barred owl, the state's most vocal

owl. This large brown and white owl, with large dark eyes

and no ear tufts, is common. Barred owls also produce a startling

array of wails, screams, whoops and cackles. They are especially

noisy during their March and April courtship period. Prey

include small mammals, frogs, snakes and fish.

Great Horned Owl

Great horned owls are the real "hoot-owls."

Their large size, ear tufts, yellow eyes and white throat

bib of this owl are unmistakable. The deep, rhythmic hoots

can be heard as early as January. Their five-note call has

been likened to the phrase, "Who's awake? Me Too!" An opportunistic

predator, the great horned owl feeds mainly on mammals, including

skunk and porcupine.

Screech Owl

The screech owl is a bit larger than the

saw-whet and is also a cavity nester. These owls have two

typical calls, neither one a screech; the "whinny" is a mournful

descending whistle and the "tremolo" is a one-pitch whistle.

Screech owls feed mainly on insects and small rodents.

February 2003:

John Tweedy remarked on the incredible

ability of squirrels in his yard to find

the acorns quickly and efficiently, even under all this snow.

How do they do that?

Carol Andrews saw a flying squirrel on her

deck a few nights ago. It was eating the seeds that fell into

a hole in the snow under the bird feeder. Apparently flying

squirrels are very common, but we don't see them because they

are nocturnal.

Here are a few facts about the flying squirrel:

There are two species of flying squirrels that are likely

to be here in Washington. The northern flying squirrel prefers

conifers and the southern prefers the mixed deciduous forest.

They don't actually fly, they glide.

Flying squirrels roll their babies into balls for transportation

from nest to nest.

Northern flying squirrels grow fur on the soles of their feet

in winter.

They tend to aggregate in numbers in hollow trees (or in your

house). They are much less territorial than other rodents.

The furry vestment that drapes from wrist to ankle on each

side of the flying squirrel's body is called a patagium. The

patagium contains a complex arrangement of muscles. These

control the direction of flight. Ropelike muscles along the

outer edge hold the airfoil taut. Additional muscles are used

to hold the patagium close to the body when they are on foot.

This patagium also acts as a blanket to keep the babies warm.

Glides of 150 feet are not unheard of, and downslope distances

of 300 feet have been recorded.

Their eyes shine orange at night.

There seem to be a lot of Tufted Titmice

at the bird feeder this winter.

January 2003:

Townspeople have reported seeing groups

of moose traveling together.

Itching to get outside? Watch out for snow fleas!

"There are thousands of these little black things jumping

around on the snow in my front yard. Are they fleas?"

These little critters are referred to as "snow fleas." Actually,

they are not fleas at all. They belong to a very primitive

group of insects named Collembola (CO-LEM-BO-LA), commonly

called spring tails. The group is so primitive that they do

not possess wings. They get around by cocking and releasing

a spring-like mechanism at the tail end of their body and

by crawling.

Snow fleas are active adults from November to March. They

are most apparent when the snow pack starts to thaw in late

winter. Their black color allows them to absorb heat from

the sun. They congregate in great numbers on sunny days to

feed on microscopic algae, bacteria, and fungi on the surface

of the snow and to complete mating. As the trees absorb heat

and the snow melts away from the base of the trees, the snow

fleas move down this pathway to the leaf litter and deposit

their egg load. The young hatch in the leaf litter later in

the spring. They are less than a millimeter long and pinkish

in color. They mature throughout the summer and become sexually

active adults the following fall, usually in November. Snow

fleas do no harm! They are a part of the natural processes

that take place on the forest floor. Snow fleas are part of

that complex of organisms that break down leaf and other organic

matter. They are soil builders. They are not harmful to people

or pets and they won't contaminate foodstuff if they are tracked

into the house.

To view yearly archives of our "New In

Nature" series click on year you wish to see.

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

|