|

Do you have something

happening in your corner of Washington? - Please call a member

or e-mail your observations to have them included here

December 2006:

We have had no snow and

lots of warmth so far this month.

Nan found some good information on the NOAA website about

this strange winter weather.

This year through November, the temperatures in New Hampshire

were the 2nd warmest on record, with the month of November

ranking as the warmest month on record. New Hampshire experienced

the 2nd wettest period on record with New England as a whole

experiencing the wettest June - November.

Globally

the annual temperature for combined land and ocean surfaces

is expected to be sixth warmest on record for 2006. Some of

the largest and most widespread warm anomalies occurred in

southern Asia and North America. Canada experienced its warmest

winter and warmest spring since its national records began

in 1948.

Including 2006, six of the seven warmest years on

record have occurred since 2001 and the ten warmest years

have occurred since 1995. The global average surface temperature

has risen between 0.6°C and 0.7°C since the start of the 20th

Century, and the rate of increase since 1976 has been approximately

three times faster than the century-scale trend.

The extent

of Arctic sea ice was second lowest on record in September,

when annual sea ice extent is at its lowest point of the year.

This was only slightly higher than the record low extent measured

in 2005. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center,

this is part of a continuing trend in end-of-summer Arctic

sea ice extent reductions of approximately eight percent per

decade since 1979, when recordkeeping began.

El Nino conditions

developed in September, and by the end of November, sea surface

temperatures in most of the central and eastern equatorial

Pacific were more than 1.8°F (1°C) above average. This El

Nino event is likely to persist through May 2007, according

to NOAA's Climate Prediction Center.

All information was found

at: NOAA National Climate Research

and:NOAA 2006 Climate Research

Here is also a great article to read about

the warm winter weather and it's confusing effect on wildlife:

Seacoast Online News

November:

Mark commented on seeing large numbers

of Stink Bugs lately and wondered why there

are so many. Is it a Stink Bug Invasion?

This is one bug that knows how to get your attention. It is

noisy in flight, relatively large, conspicuously colored,

and releases a pungent odor when handled. If you have a home

in an area with coniferous trees, at one time or another you

have probably had a run-in with this creature.

People commonly refer to this insect as a “stink bug.” Although

it does have an odor, “stink bug” is not its true name. Its

technical name is Western Conifer Seed Bug (Leptoglossus occidentalis).

The Western Conifer Seed Bug (WCSB) is an intimidating-looking

insect that moves into homes in late fall to take shelter.

Although it does not bite or sting, as a member of the stink

bug family, it often releases an offensive odor when handled

— part of the insect’s defensive strategy. In flight, the

adults make a buzzing sound like a bumblebee.

In spring the bugs move back outdoors to nearby coniferous

trees to feed on the developing seeds and early flowers, using

their piercing-sucking mouthparts to pierce the scales of

conifer seeds and suck out the seed pulp. The list of host

plants includes white pine, red pine, Scotch pine, Austrian

pine, Mugho pine, white spruce, Douglas fir and hemlock. Because

these species commonly appear in home landscapes, the bugs

may take shelter for the winter in nearby homes and other

buildings.

In the spring females lay rows of eggs on needles of the host

trees. The eggs hatch in about ten days and the young nymphs

then begin to feed on tender cone scales and sometimes the

needles. Nymphs pass through five stages and reach adulthood

by late August. Adults then feed on ripening seeds until cold

weather arrives and the insects begin seeking overwintering

quarters.

If these seed bugs are a problem in your area, be sure to

screen attic or wall vents, chimneys and fireplaces so you

block their points of entry. Eliminate or caulk gaps around

door and window frames and soffits, and tighten up loose-fitting

screens, windows or doors to prevent these insects from getting

into your home. New Hampshire currently has no pesticides

specifically registered for control of WCSB. If large numbers

of these insects do invade your home, vacuum or sweep them

up and put them back outside. Information found at the

UNH Extension website

October:

This month there have been lots of

mushrooms and moose to observe.

Since we have talked in the past about the mushrooms found

in Washington, here is some information about moose.

Moose are big. An adult moose, averaging

1000 pounds and standing 6 feet at the shoulder, is the largest

wild animal in North America. Moose have keen senses of smell

and hearing, but they're also near-sighted. Their front legs

are longer than their hind legs, allowing them to jump over

fallen trees, slash, and other debris. Moose, like deer, lack

a set of upper incisors; they strip off browse and bark rather

than snipping it neatly. Bulls and cows have different coloration

patterns. Bulls have a dark brown or black muzzle, while the

cows face is light brown. Cows also have a white patch of

fur just beneath their tail.

Only bulls grow antlers. Antler growth begins in March or

April and is completed by August or September when the velvet

is shed. Antlers are dropped starting in December; young bulls

may retain their antlers into early spring. Yearlings develop

a spike or fork; adults develop antlers that may weigh up

to 60 pounds with wide sweeping palms with many long tines.

The bell (the flap of skin and long hair that hangs from the

throat) is more pronounced in adult bulls than in cows or

immature bulls.

Today there are some 6,500 moose in New Hampshire, occurring

in all ten counties with highest densities in the Great North

Woods. During a year moose home ranges vary from 5 square

miles to more than 50 depending on the season.

Each year nearly 200 moose are killed on our highways. Their

dark coloration blends well with dark pavement. To avoid collisions,

drive slow enough at night and dusk so you can stop within

the limits of your headlights illumination.This information

was found at the NH state web site, to learn more about moose

click here:

NH State Moose information

One way to support conservation and cultural

heritage in New Hampshire is by purchasing a conservation

license plate, also known as a Moose Plate.

Revenues generated are distributed to help fund projects that

focus on the protection of our state's critical resources.

The voluntary public purchase of the plates helps to ensure

that the scenic beauty, wildlife, and historic sites of New

Hampshire will be here for our children and grandchildren.

To find out more about Moose Plates click here:NH

Moose Plates

August :

Michael Pon from Washington wrote a commentary

last week in the local paper "The Villager". He

was lamenting about the recent disappearance of Red

Spotted Newts from Millen Pond and what factors may

haves caused their decline in numbers. To read his commentary

click here:The

Villager article

We wrote about these wonderful creatures

in August 2005, here is the link to learn more about them:

2005

New in Nature Archives We hope they haven't

disappeared for good! They are a favorite creature to "catch

and release" for a lot of kids in town.

Don mentioned noticing lots of local Ash trees

with die back lately. He wondered if the damage could be caused

by a recently imported foreign pest called the Emerald Ash

Borer. First found in Detroit in the summer of 2002, this

insect has killed millions of ash trees in Michigan and has

since been discovered in parts of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.The

Emerald Ash Borer's primary movement seems to be through firewood,

so you should only use local sources and don't bring in firewood

from out of state. If the spread of Emerald Ash Borer is not

controlled, it could eliminate ash trees as a species from

North America. The foresters at the N.H. Division of Forests

and Lands are keeping an eye out for these pests and others

that threaten the trees in NH.

Ticks are plentiful this summer, as anyone

with a dog will attest. The New Hampshire Cooperative Extension

Service has lots of information for you on the varieties of

ticks found in this area and what to do if you find a tick

on you or your pet: NH

Cooperative Extension - Ticks

May :

Lots of wildflowers are

blooming: fringed polygala, star flower, goldthread, foam

flower, and rhodora is just starting to bloom. (Bradford

Bog will be spectacular soon)

April:

Two Bald Eagles were seen

on Half Moon Pond the week of April 10th, one mature and one

immature. A mature eagle was also spotted on the 14th. Everyone

should keep an eye out for these magnificent birds.

The Bald Eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, is a magnificent

bird of prey that is native to North America. This majestic

eagle is not really bald; white feathers cover its head. The

derivation of the name "bald" is from an olde English word

meaning white. Bald eagles have a long, downward-curving yellow

bill, and large, keen eyes. These strong fliers have white

feathers on their head, tail, and wing tips; the body has

brown feathers. They can fly 20 to 40 mph in normal flight

and can dive at speeds over 100 mph. Adult eagles have a 7

ft wingspan and the females are 30% larger than the males.

They live and nest near coastlines, rivers, lakes, wet prairies,

and coastal pine lands in North America from Alaska and Canada

south into Florida and Baja, California. Bald eagles build

an enormous nest from twigs and leaves and may use the same

nest year after year, adding more twigs and branches each

time. The nest can be up to eight feet across and may weigh

a ton! Nests are located high from the ground, either in large

trees or on cliffs. A clutch of 1 to 3 eggs eggs is laid by

the female in the nest and both males and females incubate

the eggs. They both feed the hatchlings until they learn to

fly (fledge).

Eagles are carnivores (meat-eaters) and hunt during the day.

Their feet have knife-like talons which they use to catch

their prey. They eat mostly fish swimming close to the water's

surface, small mammals, waterfowl, wading birds, snakes, and

dead animal matter (carrion). By eating carrion they help

with nature's clean-up process and by hunting they help keep

animal populations strong. Bald eagles can actually swim!

They use an overhand movement of the wings that is very much

like the butterfly stroke. Their life span is up to 30 years

in the wild.

The bald eagle has been the national symbol of the USA since

1782, so when it became threatened with extinction in the

1960s due to pesticide use, habitat loss, and other problems

created by humans, people took notice. For years the bald

eagle was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species

Act. Now the number of bald eagles has increased so much that

in June, 1994 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed

that they be downgraded from endangered status to the less

urgent status of threatened in all but three of the lower

48 states. The success of the bald eagle is a tribute to the

Endangered Species Act and is an incentive for increased awareness

and conservation everywhere.

March:

The

beaver (Castor canadensis) is the largest rodent in North America and can tip the scales at

more than 60 pounds, although an average adult weighs 3540

pounds. An adult beaver can be nearly three-feet tall when

standing on his hind legs.

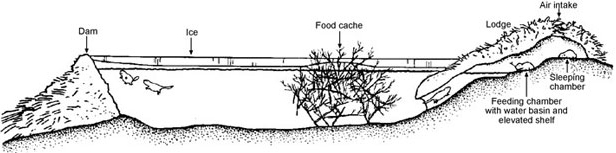

Beavers typically live in lodges constructed from branches,

mud, and other debris, or in dens dug into the banks of streams

or lakes. Lodges may be created along the edges of canals

or ponds, or formed as mounded islands of interwoven branches

that stand further out in deeper water. The structures are

packed solid with mud to make them weatherproof—except for

the peak, which is left open for ventilation—and have at least

two or more water-accessible openings. In the fall, beavers

stockpile winter food supplies by sinking large amounts of

branches into the mud close by their lodges or dens. With

a sizable underwater cache, beavers can remain comfortably

well-fed even during the harshest winter freeze. They simply

swim beneath the water's icy surface to retrieve choice branches,

then devour them inside the lodge. For beavers, dam-building

is an instinctive survival skill. The main purpose is to surround

themselves with a stable body of water—understandably important

to animals who are far more adept in water than on land. The

resulting pond provides beavers with a safe refuge from predators;

flooding an even larger area also ensures watery access to

prime food sources in the vicinity.

Beaver lodge, food cache, and dam in water

All winter the beavers bring sticks from their underwater

cache into the feeding chamber of the lodge to gnaw the succulent

bark. They prefer trembling aspen, poplar, willow, and birch.

They also swim out under the ice and retrieve the thick roots

and stems of aquatic plants, such as pond lilies and cattails.

During mild winters and warm days in March and early April,

adult beavers emerge from their dull aquatic world to feed

on fresh woody stems along the shore. Beavers shift from a

woody diet to a herbaceous diet as new growth appears in the

spring. During summer, beavers will eat grasses, herbs, leaves

of woody plants, fruits, and aquatic plants.

Information found at:

Humane Society of the United States website

February:

Lady beetles, often called Ladybugs or coccinellids,

are the most commonly known of all beneficial insects. In

Europe these beetles are called "ladybirds." There are nearly

5,000 different kinds of ladybugs worldwide, 400 of which

live in North America. The ladybug is the official state insect

of New Hampshire, Delaware, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Tennessee.

Both adults and larvae feed on many different soft-bodied

insects with aphids being a ladybug's favorite food. More

than 5,000 aphids may be eaten by a single adult ladybug in

its lifetime. Ladybugs chew from side to side and not up and

down like people do. If you squeeze a ladybug it will bite

you, but the bite won't hurt. A ladybug will play dead if

it is threatened. They also make a chemical that smells and

tastes terrible so that birds and other predators won't eat

them.

The male ladybug is usually smaller than the female. A female

ladybug will lay more than 1000 eggs in her lifetime and she

lays her eggs only where she knows there are aphids present.

Ladybugs usually do not have their spots for their first 24

hours of adulthood, so if you see one without spots, it may

be a brand new adult. The spots on a ladybug fade as the ladybug

gets older.

During the autumn, ladybugs crawl to over wintering sites

where a few to several hundred will gather in an aggregation.

They congregate in large numbers on the sunny side of the

house then they will enter the house through any small opening

to find a corner and hibernate. During hibernation, ladybugs

feed on their stored fat. If the humidity is ample in your

home, they will survive and fly away in the springtime. Ladybugs

won't fly until the temperature is above 55 degrees Fahrenheit.

These little creatures live for about a year. Some people

believe that if you find a ladybug in your house in the winter

you will have good luck.

Information found at: www.geocities.com/sseagraves/ladybugfacts.htm

To view yearly archives of our "New In

Nature" series click on year you wish to see.

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

|