|

Do you have something

happening in your corner of Washington? - Please call a member

or e-mail your observations to have them included here

December:

Pileated woodpeckers are the largest of the common woodpeckers found in North America. Body size 16 to 19 in. wingspan, 26 to 30 in and weight: 8.8 to 12.3 oz.

These crow-sized birds present a memorable sight with their zebra-striped heads and necks, long bills, and distinctive red crests.

Pileated woodpeckers forage for their favorite meal, carpenter ants, by digging large, rectangular holes in trees.

These holes can be so large that they weaken smaller trees or even cause them to break in half. Other birds are

often attracted to these large openings, eager to access any exposed insects.

Pileated woodpeckers do not discriminate between coniferous

and deciduous trees—as long as they yield the ants and beetle

larvae that make up much of the birds' diet. It uses its long,

sticky tongue to poke into the holes and drag out the ants.

Woodpeckers sometimes access these morsels by peeling long

strips of bark from the tree, but they also forage on the

ground and supplement their diet with fruits and nuts. Although

the pileated woodpecker is adapted to clinging to the sides

of trees, it is a strong flyer and it will even sometimes

hop around on the ground.

The call is a wild laugh, similar to the Northern Flicker. Their enthusiastic drumming sounds

like a loud hammering, and is audible for a great distance. Woodpeckers also drum to attract

mates and to announce the boundaries of their territories. Pairs establish territories and live on them all year long.

The birds typically choose large, older trees for nesting and usually inhabit a tree hole.

In eastern North America, pileated woodpeckers declined as their forest habitats were

systematically logged in the 19th and 20th centuries. In recent decades, many forests

have regenerated, and woodpecker species have enjoyed corresponding growth. The birds

have proven to be adaptable to changing forest conditions.

The Pileated Woodpecker was the model for the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker.

This information and more can

be found at:

NH

National Geographic Animals

November:

Don was walking in the woods near his house last month when

he looked down and picked up something that looked like a

green sea urchin (spines and all), he looked around the ground

and saw another. Puzzled about what these were, he looked

up and realized that the tree he was standing next to was

an American Chestnut! It appeared to be very

healthy and was making chestnuts.

Almost all of the American Chestnuts

were killed by a blight that began attacking them early in

the 1900s. The fungus was likely introduced to North America

on nursery stock from Asia and was first observed killing

trees in the Bronx Zoo, in New York City in 1904. From there,

Chestnut blight spread rapidly through eastern North America,

and across the entire natural range of the Chestnut. An estimated

4 billion American chestnuts, one quarter of the hardwood

tree population, grew within this range.

The American chestnut

tree was an essential component of the entire eastern US ecosystem.

A late-flowering, reliable, and productive tree, unaffected

by seasonal frosts, it was the single most important food

source for a wide variety of wildlife from bears to birds.

Rural communities depended upon the annual nut harvest as

a cash crop to feed livestock. Although the nuts are smaller

than other kinds of chestnut, they are very delicious.

The

chestnut lumber industry was a major sector of rural economies.

Chestnut wood is straight-grained and easily worked, lightweight

and highly rot-resistant, making it ideal for fence posts,

railroad ties, barn beams and home construction, as well as

for fine furniture and musical instruments.

Early attempts at controlling Chestnut blight involved crossing

the Chinese Chestnut with the American Chestnut, in hopes

that some of the hybrids would show resistance as well as

the upright form of the American Chestnut. It wasn't very

successful. Recently, a new program involving several generations

of backcrosses to the American chestnut was initiated in another

attempt to breed resistance with good tree form. The American

Chestnut Foundation is working hard to bring back this magnificent

tree.

Visit their website to learn more: American Chestnut Foundation

And watch out for those "sea urchins" in the woods!

October:

Jed heard and then saw a large "roost"

of crows in East Washington. Just before he took

this picture he said there were literally ten times as many

birds sitting in the trees and he caught this big group as

they were taking off. They may have been chatting about the

great meal they just ate in the Eccard's corn fields.

The crow is a big, glossy, black colored bird approximately

17 to 20 inches long with a strong stout build and a compressed

bill. On a bright sunny day, crows sometimes look dark purple.

They range all over North America, and are well-adapted to

diverse habitats.

They thrive in mountains, woodlands, across plains and farmers'

fields, and throughout urban areas. They are omnivorous -

they will eat anything edible, and many things which aren't.

Their regular diet includes animal and vegetable matter, insects,

crops (especially corn), and occasionally the eggs or young

of other birds. They also scavenge carrion, garbage, and eat

wild and cultivated fruit and vegetables.

Despite their bad reputation for eating crops, crows also eat a number of pests which are

harmful to those same crops, including cutworms, wireworms, grasshoppers and even noxious weeds.

The crow is one of the most intelligent of all birds.Their

intelligence is apparent in their ability to communicate a

wide range of messages with their call. A crow can communicate

warning, threat, taunting, and cheer to other crows by varying

the “CAW” sound it makes. Their cries of warning are specific

enough that some animals other than crows are also able to

use them as signals of dangerous predators.

They will congregate into huge flocks of up to several thousand

in fall and winter. These large flocks are the result of many

small flocks gradually assembling as the season progresses,

with the largest concentration occurring in late winter.

Crows are smart, quite adaptable and noisy neighbors that

can be lots of fun to observe.

September:

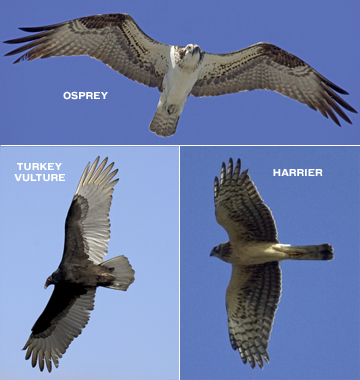

Photos by Lillian Stokes

September is considered by many birdwatchers as the month

of the Hawk, for it is when hawk migration

is at its peak. Hawks journey over many thousands of miles

from their summer breeding grounds to their winter quarters

and many of them travel together.

The birds known as diurnal raptors are birds of prey that

are sometimes referred to simply as “hawks.” They include

eagles, falcons, ospreys, kites and harriers as well as hawks.

Among thirty-two species that occur regularly in North America,

at least twenty are migratory moving seasonally to exploit

food resources. They range in size from the diminutive American

kestrel (not much bigger than a robin) to the massive bald

eagle with a wingspan of more than six and a half feet.

Many of these birds travel long distances, migrating from

Canada to South America. During these annual migrations they

often gather in huge numbers along coastlines and mountain

ridges where geography and local weather interact to bring

them together. At these special places, biologists, citizen

scientists, birdwatchers, and the interested public also gather

to identify and count these raptors or simply to enjoy one

of nature’s most magnificent spectacles.

One place you can do this locally is New Hampshire Audubon's

Pack Monadnock Raptor Migration Observatory, located

on the summit of Pack Monadnock in Miller State Park in Peterborough.

Pack Monadnock is one of several locations in the state where

large numbers of migrating hawks are regularly seen in the

fall; more than 10,000 hawks were counted from the Observatory

in 2006. The auto road to the summit parking lot in Miller

State Park allows almost anyone to reach the Observatory and

experience this spectacle firsthand.

A short improved trail leads from the parking lot to the site

of the Observatory where there is a stable outdoor observation

platform with rock benches. Large interpretive panels describe

the project and provide visitors with a full-color key to

identifying the raptors of New England. The best days for

viewing are warm and sunny, with winds from the northwest,

especially during early to mid-September. The Observatory

is open and staffed every day from September 1 to October

31. You are invited to visit and watch the show of migrating

hawks and learn all about it.

This information and more can

be found at:

NH

Audubon Migrating Hawks

August:

Photo by the National Park Service

Someone mentioned seeing a pair of bear cubs

out near Journey's End. Mama bear wasn't spotted but chances

are she was near by.

Bear cubs are born in winter dens during January after a gestation

period of about 8 months. Newborn cubs are born hairless,

with eyes closed, measuring 6-8 inches in length, and weigh

less than 1 pound. Cubs stay with their mother for approximately

18 months and den with her again during the following winter.

When they are a year and a half old, cubs leave their mothers

prior to the June/July mating season.

Mother bears are rarely aggressive toward humans, but they

are protective of their cubs. A mother bear will usually give

many warning signs (huffing or popping sounds, swatting the

ground or even bluff charges) to let you know that you are

too close. Move away as described below.

If you see a bear, keep your distance. Make it aware of your

presence making sounds. If you get too close to a bear, it

may slap the ground, huff, blow and chomp its teeth or rush

you (this is referred to as "bluff charge") in an attempt

to get you to move a more comfortable distance away. If this

occurs, maintain eye contact with the bear, speak in a soft,

calm voice and slowly back away from the bear. These actions

will help appease the bear and show that you are not weak,

but, at the same time, not a threat to the bear. Do not run,

avert your eyes or turn your back to the bear. The bear may

perceive weakness and enforce dominance. The bear's bluff

charge and chomping of teeth are a defense mechanism to establish

the bear's dominance in an encounter with humans or a more

dominant animal in the wild. Bears can outrun, out-swim and

out-climb you. If you are attacked by a black bear, you should

fight back rather than "play dead."

Black bears are capable of killing people, but it is an extremely

rare occurrence. The last time someone was killed by a black

bear in New Hampshire was 1784. Black bears, like all wild

animals, should be treated as unpredictable animals.

Here are a few tips:

• Normal trail noise should alert bears to your presence

and prompt them to move without being noticed. However, if

you see a bear, keep your distance. Make it aware

of your presence by clapping, talking or making other sounds.

• If a bear does not immediately leave after seeing

you, the presence or aroma of food may be encouraging it to

stay. Remove any sight or smell of foods.

Place food items inside a vehicle or building. Occupy a vehicle

or building until the bear wanders away.

• Black bears will sometimes "bluff charge" when cornered,

threatened or attempting to steal food. Stand your

ground and slowly back away.

• Enjoy watching black bears and other wildlife

from a distance. Respect them and their right to

live in wild New Hampshire.

• Black bears do not typically exhibit aggressive

behavior, even when confronted. Their first response

is to flee. Black bears rarely attack or defend themselves

against humans.

This information and more can

be found at:

NH

Wildlife Bear Facts

Learn

to Live With Bears

Frequently

Asked Bear Questions

July:

Purple loosestrife is

native to Eurasia. It was originally introduced to eastern

North America in the early to mid 1800's. One of the most

persistent invasive plant species in New Hampshire is also

widely regarded as one of the most beautiful.

It is a perennial herb with a square, woody stem and opposite

or whorled leaves that grows to between 3 and 6 feet tall.

Purple loosestrife flowers from July through August in New

Hampshire, and is named for its bright purple flower that

spikes from the top of the plant. One plant may grow as an

individual stalk or as several stalks clumped together.

Invasive plants share several characteristics that help them

thrive and dominate in new environments. Most invasive plants

produce a lot of seed-a single purple loosestrife plant can

produce 2 million viable seeds per year, have aggressive root

systems, colonize in disturbed areas, and are habitat generalists.

Optimum habitats include freshwater marshes, open stream margins,

and alluvial floodplains. Purple loosestrife also occurs in

wet meadows, river banks, and edges of ponds and reservoirs.

It favors fluctuating water levels and other conditions often

associated with disturbed sites, such as construction sites

for docks or marinas. Purple loosestrife is often associated

with cattail, reed canary grass, and other moist soil plants.

Purple loosestrife is a problem because it negatively affects

wildlife and agriculture. Purple loosestrife displaces and

replaces native flora and fauna, eliminating food and shelter

for wildlife. By reducing habitat size, purple loosestrife

has a negative impact on fish spawning and waterfowl habitats.

The plant also diminishes wetland recreational capability.

Purple loosestrife affects agriculture by blocking flow in

drainage and irrigation ditches and decreasing crop yield

and quality.

If you find purple loosestrife pull or dig it up, first year

plants are easy to pull. It can be difficult to pull established

plants, owing to the extensive root mat. Plants will resprout

unless the entire root is removed by digging. Time your attack

before it flowers or just as it starts flowering from the

bottom up. Later than this allows the plant to make seeds

which spread quickly. If you need to see the flowers before

digging, do so but burn or bag your Loosestrife for disposal.

Do NOT compost it.

More information can be found

at:

NH

DES site

NH

DOT Report on Purple Loosestrife

Invasive

Plants in the Upper Valley

June:

Turtles!

What to do if you find a turtle

crossing the road

From the end of May to the end of June, New Hampshire motorists

and pedestrians are very apt to meet turtles in the middle

of the road. At this time of year, they are females out to

lay eggs, a biological imperative that must be obeyed. Often

people have a commendable desire to help these slow-moving

creatures out of a risky situation. In that case, it is best

to move the turtle to a safe place in the direction in which

she was heading. It is also important to keep in mind that

turtles have a home range and females often return to the

same general area to lay eggs. Removing the turtle from the

place where she is found and taking her to an area that seems

"safer" is therefore not a good idea.

Snapping turtles tend to be out early in

the day. These are large, solid-colored turtles with pointed

heads and a line of bumpy spines going down the center of

their long tails. Although smaller ones may be safely carried

by the tips of their tails with outstretched arm and the bottom

shell (plastron) facing you, treating larger ones this way

may cause injury to their tails and they should be carried

by their back legs instead. Given their surprisingly long

necks and strong jaws, however, many of us feel hesitant about

getting up this close and personal. If traffic is light enough

to make it possible, use a stick to gently tap the edge of

the shell near the tail to try to hasten the turtle to the

side of the road. Bear in mind that a turtle, even when hastening,

isn't moving very fast. If this is not feasible, it might

be a good idea to keep a snow shovel in your car for carrying

purposes. After all, who is to say that it won't snow in New

Hampshire in May or June?

In the afternoon the turtle most often met is the familiar

Eastern Painted Turtle with yellow and red

head markings and red on the edges of the top shell (carapace).

This species does not pose any danger. If small, the painted

turtle may be safely lifted and carried by the edges of her

shells with one hand; larger ones should be moved using two

hands with the fingers holding the bottom shell and the thumbs

on the top. Most painted turtles respond to being lifted by

tucking themselves into their shells but some are apt to move

their feet rapidly in an effort to escape. Be prepared for

this reaction so you are not startled into dropping the turtle

and causing harm. - This information

and more found at: NH

Audubon Society

More about turtles:General

information on turtles of New Hampshire

Information

on turtle conservation

May:

American Kestrel,

Photo credit: USFWS

Mark had an American Kestrel hang out with

him for about 5 hours when he was working outside one day.

He said it was not shy at all and kept landing on his equipment

(which was running at the time) and flying around between

the barn and the yard. Carol said that Kestrels like to hang

out around farms eating small rodents and birds, and bugs.

They are approximately 9-12" in size and recognizable in all

plumages by a rusty tail and back. The adult male has slate-blue

wings and the female has rusty wings and back with narrow

bands on tail. Both sexes have 2 black stripes on face.

Unlike larger falcons, the "Sparrow Hawk" has adapted to humans

and nests even in our largest cities, where it preys chiefly

on House Sparrows. In the countryside it takes insects, small

birds, and rodents, capturing its prey on the ground rather

than in midair like other falcons. Kestrels are active during

the day and prefer an "open country" habitat found in fields,

heaths, and marshland. When hunting, the Kestrel hovers, almost

stationary, about 10-20 m above the ground searching for prey.

Once prey is sighted, the Kestrel makes a short, steep dive

toward the target.

Kestrels use old nests of other birds or nest in holes in

trees, cliff ledges or even man-made structures, such as bridges.

3-5 eggs are laid around late April to May, with about two

days between each egg. The female does most of the incubating

and is fed by the male. The male calls as he nears the nest

with food; the female flies to him, receives the food, and

returns to the nest. After the eggs hatch, the male continues

to bring most of the food. The young stay with the adults

for a time after fledging, and it is not uncommon to see family

parties in late summer.

April:

This picture of Earth is provided by NASA's

Terra satellite. Terra is the flagship of NASA's Earth Observing

System, a series of satellites gazing down on our planet from

the unique vantage point of space. You can find more beautiful

shots of our planet here:

NASA Terra and

Visible Earth

In honor of Earth Day on April 22nd why don't

we all try to "Go Green" in a few little

ways to help out the earth and conserve our natural resources.

The following are web links with suggestions for a few things

you can do every day to help fight waste and warming and make

your environmental footprint smaller.

Here are some "GO GREEN" web links:

Tree Hugger

guides - "Tree Hugger's guides to going green" Tons

of guides and tips for going green. Don't be afraid of this

one just because it's called "Tree Hugger", there is a wealth

of information here on many subjects.

GreenWorksGov - GreenWorksGov is a blog about how to organize a “green office” program and what to do to make “green” a reality.

World Watch

Tips - "Ten ways to go green and save green"

Recycling tips - All about recycling, what it is , how to do it, why it is important

the

EPA's Green Shopping tips - Ways to go green while

shopping

For Teachers:

Go Green Initiative - Ways to implement a Go

Green Initiative at school and get kids involved in environmental

responsibility

Green work place

choices - Ways to help your workplace make green

choices

Sierra Club's Green workplace choices "10 Ways

to Go Green at Work"

Lighter

Footstep "Ten first steps toward a lighter, more

sustainable lifestyle"

For your Power - Recycle — Save Energy, Resources and the Environment

Eco Friendly

gifts - Eco Friendly Gift Bags

Natural Resources Defense Council - Actions you can take in your daily life

Water Resource Use - Information about wise use of water resources

Water Conservation - Water conservation whys and hows

Solar and Renewable power - Facts about solar energy and renewable resources

For Kids:PBS for kids - PBS site with lots of info, games, and links for kids

EPA's site for Kids of all ages

For Teens:Youth

Noise - Sustainability challenges to live a more

eco-concious lifestyle.

The Story of Stuff - The Story of Stuff project, all about bottled water and more movies

Now go surf the web and see what else YOU can find and good

luck going green! Little changes in your life style add up

to big savings and a healthier planet!

March:

Both Mark and Nan reported recently seeing

weasels running across the snow in different

locations. We wondered what kind of weasels they could be

and we were surprised to find out that New Hampshire has weasels

in abundance with 6 members of the weasel family living here.

Which one of the winter weasels were they? The family includes

(from smallest to largest): Ermine (also known as the short-tailed

weasel), Long-tailed weasel, Pine marten, Mink, Fisher and

River otter. All of these, except the marten, are common to

abundant throughout most of New Hampshire, but most of us

can count on our hands the number of times we have seen any

one of them. They may be abundant, but are scarce to our view.

Two species, the ermine and long-tailed weasel, disappear

nearly completely in winter by turning white as snow! If you

can spot any weasel, then you are doing remarkably well!

Weasels, by their very nature, keep themselves scarce. Most

of them are either most active after dark, or, as in the case

of the otter, are active at first light of morning. They leave

an abundance of sign in our forests or along our rivers. When

the Fish and Game Department did numerous winter snow tracking

census lines in the early 1980s, fishers were the most frequently

observed tracks -- even more common than squirrels! Fisher

are found practically everywhere there is plentiful cover

of softwoods, including our backyards. Their distinctive two-two-two

(: : : :) cantered prints in the snow leave ample signs to

find. Learning the signs of these small predators will open

a whole new world of wildlife for you to discover in your

area.

-- Eric Orff, wildlife biologist,

N.H. Fish and Game

Lots more information about these

6 weasels can be found here: New

Hampshire Fish and Wildlife Website

February:

Mark reports seeing bobcat tracks

up in the hilly, wooded area above the corn field. It appeared

to him that the Bobcat was chasing down a squirrel but wasn't

successful in making a meal of it.

The Bobcat is the last survivor of three

wildcats that once roamed the New Hampshire woods. Mountain

lions (also called cougars, panthers or catamounts) were gone

from the state by the late 1800s. The bobcat's taller cousin,

the lynx, lived in northern New Hampshire through the 1950s.

Today, only the tenacious bobcat is still here. No one knows

for sure, but probably several hundred bobcats still live

in the Granite State. The southwestern corner of New Hampshire

has the most consistent reports of bobcat sightings.

For centuries, bobcats were killed for bounty in New Hampshire,

and by the late 1970s, bobcats had become scarce. New Hampshire's

hunting and trapping seasons for bobcat were finally closed

in 1989. In less than a decade, bobcats went from being bountied

in New Hampshire to being completely protected.

The bobcat population in New Hampshire has increased since

that time, but not by much, because now the state's bobcats

face new challenges. Fishers and coyotes compete with bobcats

for a dwindling prey pool, and encroaching development breaks

up the large blocks of habitat bobcats need. Humans have ushered

in another dangerous element: busy roads that can be deadly

for the wide-ranging animals.

Bobcats often roam between brushy swamp areas and the high-elevation

habitat they prefer. Rocky, south-facing slopes and near-summit

ledges of mountains offer protection, a safe place to raise

kittens and a chance to soak up the sun. The bobcat's only

real social grouping is females with kittens -- usually about

3 to a litter, dependent on their mothers for 9 or 10 months.

This solitary lifestyle means bobcats need space, and lots

of it. Females stake out a territory of about 12 square miles,

and males roam over about 36 square miles. A lot depends on

the availability of food -- snowshoe hare and cottontail rabbits

are the bobcat's favorite, though they will eat mice, chipmunks,

wild turkeys and even an occasional deer. Ongoing efforts

to conserve, connect and manage protected lands continue to

be the best bet for helping New Hampshire's last wildcat survive.

Winter is an especially tough time for bobcats in New Hampshire.

Food is scarce, and the bobcat's short legs and small feet

aren't well suited to hunting in deep snow. Driven by hunger

during the cold months, bobcats sometimes gravitate to barns

and porches in search of food, or stalk birds and squirrels

at backyard feeders. Many young bobcats, as well as some adults,

don't survive winters with long periods of deep, fluffy snow.

Information found at: NH

Wildlife reports

January:

Here's a Bright idea for the new

year!

In the United States, we use one-quarter of our average home

energy budget in electricity for lighting. Most of that electricity

powers incandescent lightbulbs, which are notoriously inefficient.

If you replace your incandescent light bulbs with compact

florescent lights (CFLs) you conserve energy by yielding three

to four times the amount of light as incandescents for every

watt they consume. That's 75 percent less energy than incandescent

bulbs. Since they're so long-lasting, you'll only replace

one CFL for every 13 incandescent bulbs you use, saving resources

and landfill space. Plus, for every one CFL you install, you'll

keep 180 pounds of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas,

out of the atmosphere. You won't just be doing the environment

a service - you'll save $25 to $45 in energy costs for each

CFL you use.

A typical Energy Star® rated Compact Fluorescent Light

(CFL) lasts up to 10 times longer than an incandescent bulb,

meaning fewer bulb changes for a hard-to-reach light fixture.

Energy Star® CFLs come in a variety of shapes, color temperatures

and brightness. They screw into standard sockets, and give

off light that looks just like the common incandescent bulbs

- not like the fluorescent lighting we associate with factories

and schools. They are safer because they burn at a lower temperature

(100 degrees F) than incandescent and halogen lights, which

can burn at temperatures up to 1000 degrees F.

PSNH promotes the use of CFLs with the nhsaves Lighting Catalog.

You can look for energy efficient lighting fixtures and bulbs

in the latest issue of this catalog, which features lighting

and other energy saving products for an efficient, comfortable

and safe home. PSNH customers can shop the catalog online

at

nhsaves.

To obtain a copy through the mail, call 1-877-647-2833 or

provide your name and address information on this nhsaves

catalog request form and a catalog will be mailed to you.

Look for the Energy Star® logo whenever you buy appliances

or energy consuming products, it will help you save money

and help the environment!

To view yearly archives of our "New In

Nature" series click on year you wish to see.

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

|